Prince George Medical Staff Physician Association, University Hospital of Northern BC

In 2021, the EQUIP Health Care research project conducted in three BC emergency departments including in Prince George, shared findings on health inequity issues that affect Indigenous people and others seeking care. It shone a light on opportunities for change in emergency departments, often the first point of entry for many people accessing medical care and inpatient treatments, and when patients are at their most vulnerable.

In 2021, the EQUIP Health Care research project conducted in three BC emergency departments including in Prince George, shared findings on health inequity issues that affect Indigenous people and others seeking care. It shone a light on opportunities for change in emergency departments, often the first point of entry for many people accessing medical care and inpatient treatments, and when patients are at their most vulnerable.

The University Hospital of Northern BC (UHNBC) in Prince George is in a unique position to help create long-term and sustainable approaches to address these issues. It is the largest teaching hospital in Northern BC for health care providers of the future, and is located in the region with the highest Indigenous population in the province.

At the same time, the work of the Prince George Medical Staff Physician Association (PGMSPA) is a collaborative and integral part of helping to build toward equitable and culturally safe care.

Catalyst for change

A foundation for change was established in 2018 when Dr Terri Aldred[1] pioneered the PGMSPA’s Cultural Safety and Humility work (currently led by Dr Todd Alec). In 2019, ER physician Dr Christina Boucher began to lead the cultural safety and humility work in the Emergency Department (ED). Dr Boucher is a non-Indigenous person who seeks to be an ally and advocate for issues of inequity in health care delivery concerning Indigenous people.

With PGMSPA Facility Engagement funding to cover physician time, she took several steps to get started. She first spoke with Dr Aldred about her vision. “Dr Aldred told me about her group, the identified need for physician peer support in the ED. This foundational work helped guide me in developing my ED work.”

Dr Boucher reviewed the EQUIP research project to better understand specific health equity issues in the ED. She also gained insights from In Plain Sight "Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care" that reported on issues of inequitable health care access and outcomes endured by Indigenous peoples in BC in health care settings.

Dr Boucher then connected to work being done in Northern Health to incorporate into planning, including initiatives and resources offered by Northern Health’s Indigenous Health team to support learning and self-reflective practice among all physicians and employees.

Building an inclusive working group with Indigenous voices

In order to foster and sustain change, full representation of all vested voices was needed to source and articulate issues and work together on solutions.Dr Boucher assembled a collaborative, diverse working group (see below) representative of virtually all interdisciplinary positions working in the ED.

In order to foster and sustain change, full representation of all vested voices was needed to source and articulate issues and work together on solutions.Dr Boucher assembled a collaborative, diverse working group (see below) representative of virtually all interdisciplinary positions working in the ED.

Most importantly, the group needed to include Indigenous community members who rely on the ED and have lived experience as Indigenous people, whose participation required having trusted voices from the Indigenous community engaged in the work.

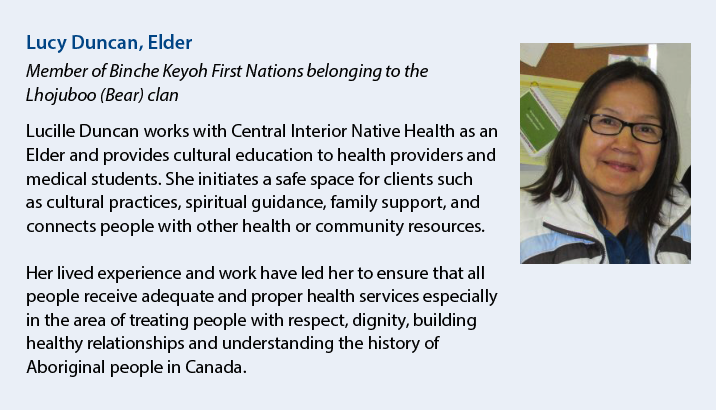

Through Dr Montana Halliday, Dr Boucher reached out to Lucy Duncan, an Elder working at the Central Interior Native Health Society and a well-known member of the Indigenous Prince George community. Lucy has also contributed to the EQUIP Health Care work, which seeks to ensure health equity within BC’s health care system.

Lucy joined the working group as an Elder and also spread the word to Indigenous community members to add their voices, particularly patients who experienced care in the hospital ED.

WORKING GROUP

- Elder, Central Interior Native Health Society

- 2 MSA physicians

- Northern Health staff: ED Program Leads (x2), Social Worker, ED Nurse, Acting ED Manager

- Indigenous Psychiatry Resident

- Indigenous patient

- Indigenous artist

- College of New Caledonia Aboriginal Resource Centre representative

- Former Chief, Stellat’en

- Elder Teacher, Lheidli T’enneh

- Aboriginal Patient Liaison

- Central Interior Native Health Services, Nurse Health Care Coordinator

- University of Northern BC / EQUIP researcher / Nurse Practitioner

"I was excited to join and expand on the work I’ve been doing with other health providers. It’s important to understand historical racism and its impact, if we want to build a better health care system that serves everyone.

...It is important to have Elders from the community with lived experiences as part of the group," she notes. "It is through their participation that open communication can happen about what Indigenous people want to experience in the ED and what barriers they have faced.” - Lucy Duncan

Feeling and finding purpose through truth telling and relationship building

The group agreed to meet monthly, and to start their work by creating an authentic foundation for change through relationship building and storytelling. The meetings place an emphasis on connection before content. Meetings start with introductions and check-ins, followed by open space for Elders and Indigenous community members to talk and share.

She emphasizes the importance of truth-telling to build understanding and support for action to address Indigenous-specific inequities in care. “The challenge is to be sure you are working on the real issues that will make culturally significant change – so it’s important to verify with the community."

"I have learned this year from the Elders on our group that relationships and trust are foundational, and are the most important activity when coming together as a group." - Dr Christina Boucher

Between meetings, Dr Boucher spends a lot of time checking in with each working group member about thoughts and feelings that have come up in the meetings. She notes that each person reacts differently, as personal, emotional stories are shared.

In her experience, she finds that talking about cultural safety and cultural humility can be challenging on a social and emotional level. It is a personal journey that takes time, and trust, and cannot be rushed."

It takes time to work through emotional contexts in order to even feel safe with one another, let alone to talk about all the details and processes involved in making the environment safe for all.

From there, the group can start to formulate action items that have arisen from the discussions.

"I see the activities of the working group prompting people in our department to engage in the self-reflective process of developing cultural humility.

Space and time are needed to build trust, create understanding, and shift beliefs to create sustainable change.“ - Dr Christina Boucher

Changing mindsets leading to positive change

The First Nations Health Authority's "Creating a Climate for Change" describes cultural humility as "a process of self-reflection to understand personal and systemic biases and to develop and maintain respectful processes and relationships based on mutual trust. Cultural humility involves humbly acknowledging oneself as a learner when it comes to understanding another’s experience."

Dr Boucher uses this sentiment to approach thinking about practical steps to take as a health care provider: “As a non-Indigenous person, I try to approach the world with an open curiosity. I hope to be an ally and advocate for the Indigenous people who are my patients, and my patients’ family members."

"I hope to continue working on identifying my personal biases and the systemic barriers that contribute to the inequity of care the Indigenous people have historically received, to make some positive improvements.”

Asked how this work could be expanded to other communities, Lucy Duncan says,“we need to build credibility with other communities by initiating the working group’s recommendations, such as an Indigenous Patient Liaison working in the ED, and showing the positive changes happening in Prince George.”

She hopes to one day see a health care system that puts aside personal biases, and provides care in a safe environment that includes dignity and respect.

"It is only through acknowledging our past can we move forward to a better future." - Lucy Duncan

Taking action: building blocks for change

Discussions have led to the following action items:

-

Plans to redesign the ED space to be more inviting to the Indigenous community, for example working with a local artist to create drums and relevant artwork.

-

Advocating with Northern Health for an ED-specific Indigenous Patient Liaison position who would assist indigenous patients to navigate through the ED and access care.

-

A proposal for cultural safety training for the security company working in the ED.

-

Using video monitors in the ED to display information about community resources and supports.

-

Sharing culturally significant learnings from the monthly meetings with ED doctors and nurses, as well as community urgent care clinics and physicians in other Northern Health hospitals and communities.

[1] Dr Terri-Leigh Aldred is the Medical Director for Primary Care for the First Nations Health Authority. She is leading community-based First Nations Primary Care Initiatives (FNPCI), as well as the First Nations Virtual Doctor of the Day (VDOD) and First Nations Virtual Substance Use and Psychiatry Services (VSUPS) to engage medical affairs matters related to our programs.

This work has been supported with funding from the Specialist Services Committee Facility Engagement Initiative, one of four joint initiatives of Doctors of BC and the Government of BC.

Discover engagement strategies and ideas from across BC to adapt and support your engagement work! Go to Knowledge Sharing>

Discover engagement strategies and ideas from across BC to adapt and support your engagement work! Go to Knowledge Sharing>  entres.

entres.

For about 20 years, the Royal Columbian Hospital (RCH) was the unofficial referral centre to help treat Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS), a serious pregnancy condition that occurs when blood vessels and other parts of the placenta grow too deeply into the uterine wall.

For about 20 years, the Royal Columbian Hospital (RCH) was the unofficial referral centre to help treat Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS), a serious pregnancy condition that occurs when blood vessels and other parts of the placenta grow too deeply into the uterine wall.

In 2021, the

In 2021, the

In order to foster and sustain change, full representation of all vested voices was needed to source and articulate issues and work together on solutions.Dr Boucher assembled a collaborative, diverse working group (see below) representative of virtually all interdisciplinary positions working in the ED.

In order to foster and sustain change, full representation of all vested voices was needed to source and articulate issues and work together on solutions.Dr Boucher assembled a collaborative, diverse working group (see below) representative of virtually all interdisciplinary positions working in the ED.